Since its birth as a science

Criminology has always been in constant "transition" and "transformation". In the 20th century, Criminology shifted its key research points from biologist theses to psychological and social perspectives. In addition, the introduction, from the second half of the century, of the mechanisms of the process and social control, supposed an important change of focus from the etiological theories and investigations to the theories of the process: The causes of the crime largely give way to protagonism to the analysis of the process by virtue of which the behavior is defined as criminal and the subject is labeled as delinquent.

The same has not happened, however, with the attitudes of the criminologist and the functions corresponding to Criminology, which have remained more or less unchanged until the beginning of the 21st century, a moment from which the need for a radical turn becomes clear. in what has been the traditional approach to criminological theory and practice.

Contemporary Criminology faces a rapidly changing world. The speed and depth of these changes must necessarily be reflected in a transformation of the subjects of Criminology. The restructuring of economic and social relations, the fluidity of social processes, the speed of technological change, and the cultural and social heterogeneity typical of postmodernity pose important challenges for Criminology, challenges that can be very complicated, but which are too insistent to be ignored.

During most of the 20th century, the analysis and fight against crime and violence has been carried out from the internal perspective of the States themselves and, with the exception that in this sense the theories of tension and Critical Criminology , as a problem disconnected from culture and the very structure of society. It is a Criminology that has been interested mainly in groups or individuals, preferably men, who commit crimes in their social environment, at home or at work against their family, neighbors, workers, colleagues or community.

But in addition, the last decades of the last century have been characterized by considering the problem of crime as a "scourge" on which "war" must be declared. Expressions used by governments such as the "war against crime", the "war against terrorism" or the "war against drug trafficking" reveal the confrontation between "us" and the "enemy", in a clear neo-punitivist expression that , for the sake of security, comes to justify that Criminal Law can and should reach all corners of society.

As Lanier and Henry state, this opposition between us and the enemy is nothing more than a simplistic analysis of reality. The social changes that have occurred in recent years have shown that the increase in interpersonal connections, not only national but also global, implies that the security of each one of us is intimately connected with the security of all the others, so we must think about problems and their solutions, including crime, at a triple level: local, national and global.

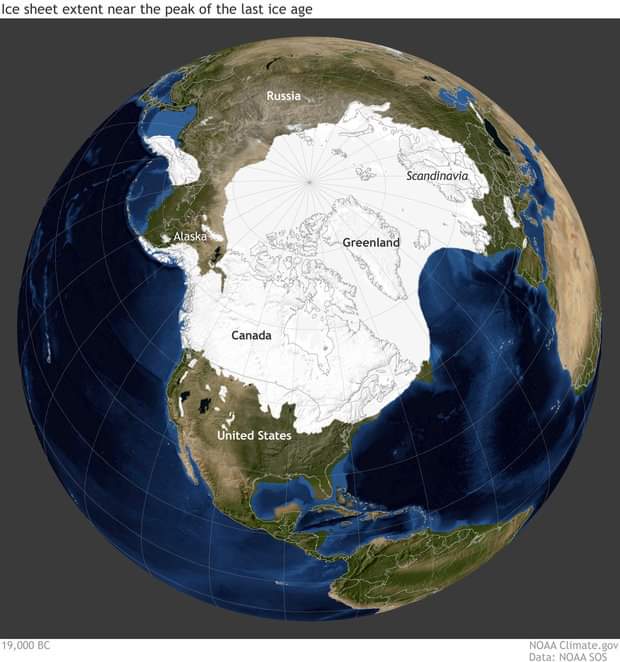

Globalization, as a process of global integration, implies that people act and solve their problems according to points of reference that are beyond their own society. As Aranberri Aresti points out, as a phenomenon of social, political, economic, and technological interaction, no one is alien to this phenomenon, which is why security and crime are also the object-subject of globalization. The security so intimately linked to human beings in their double dimension as individual beings and as social beings could not be separated from this new process. Neither does delinquency, inasmuch as it has its referent in a specific social model.

The nature of crime has changed significantly in just two decades, the change experienced in the field of organized crime being especially significant. The quasi-industrial and highly hierarchical structure of organized crime has spread globally in the shadow of international business in a diffuse network of connections, each of them involved in a whole series of legal and illegal operations. The planetary dimension of this system of connections means that an event that occurs in one place can have a significant impact anywhere else in the world. In short, crime has become global, and just as globalization has benefited international business, it has also benefited organized crime.

Globalization, supported in its economic aspect by the belief in the free market for the allocation of resources, has only been possible thanks to the revolution in the field of telecommunications and transport. The revolution in transportation has made possible the massive, rapid and cheap movement of goods and people throughout the world; and the Internet revolution has managed to globalize service infrastructures such as that of banks and financial institutions.

The freedom of the market and the revolution in transport and telecommunications have brought about major changes on a global scale: The substitution of hierarchical organizations for network connections has given rise to two phenomena that, while favoring legal trade, also favor illicit trade, and consequently the globalization of crime: On the one hand, the outsourcing or contracting out of the company's own services insofar as it allows key functions to be carried out outside the formal structure of the organization; and, on the other hand, relocation by virtue of which these key functions can be carried out anywhere in the world

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)